- 1

- 2

- next ›

- last »

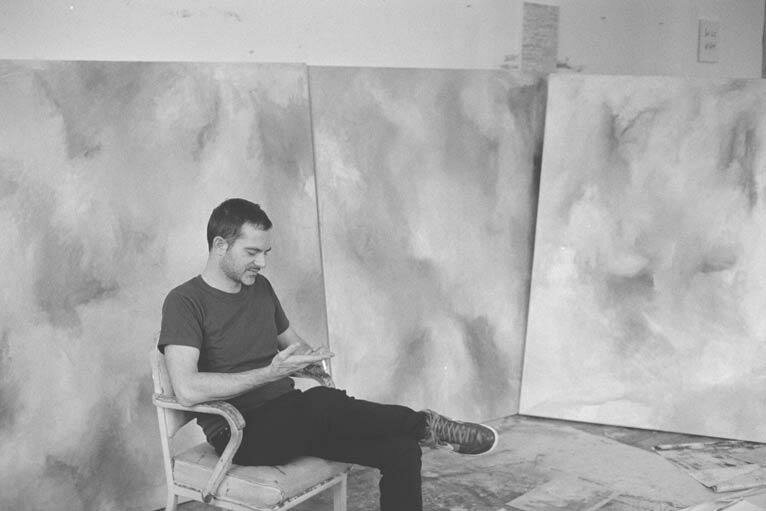

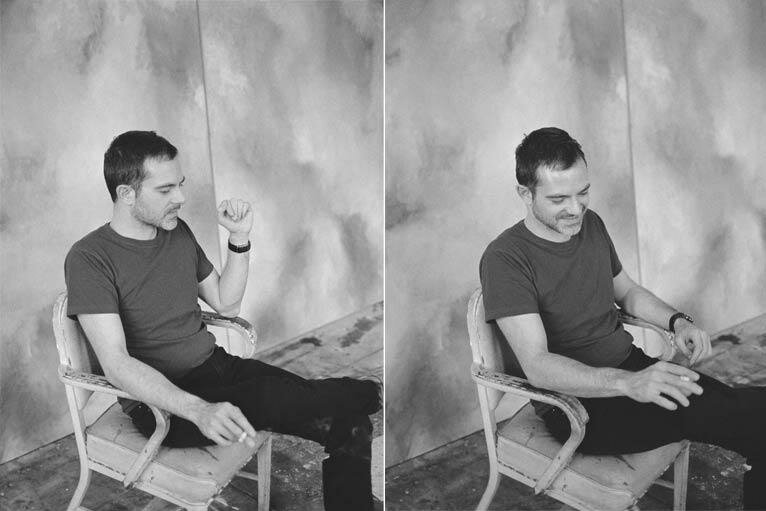

Jean-Baptiste Bernadet is an artist who flexes his creative muscles across the realms of painting, sculpture and working with choreographers as an assistant for dramaturgy, lighting and stage. Born and raised in Paris he moved to Brussels in 2000 to finish art school. Currently he can be found working in New York where photographer Clément Pascal was lucky enough to capture the artist in-studio before he takes up residency at Marfa this Spring.

Megan Christiansen: What drives you to make art?

Jean-Baptiste Bernadet: I guess I can’t do anything else. I was a very agitated kid, very active and creative, exuberant, extroverted, a liar, a thief, I think I was almost crazy...but I’ve been lucky enough to have parents that, in a certain way, didn’t try to change me too much. Maybe they just couldn’t...or maybe they were crazy too! Then in my teens painful events, the loss of people or really intensely felt breakups calmed me down, sort of, and now I guess what drives me to make art is a mix of these two things. I still have a strong curiosity and love of people and the world, but it’s saddened and obscured by melancholy and self-awareness. I guess art is the place I can play with both sides of my personality at the same time. I read somewhere that a lot of artists are bipolar so I take it as a good start to be a little bit too!

MC: Can you tell us a little bit about the body of work you are creating at the moment?

JB: Well, I just spent six months in a residency in NYC. It’s always a problem for me when I have to prepare applications for projects or residencies, I just keep working on my stuff whenever I am without a specific project. The major part of my work is to just keep going. There are still a few “contextual” works done on site (collages using found material, or specific words or shapes that appear), but they are not planned in advance.

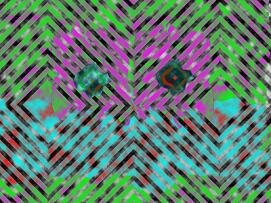

However here in NY I had a side project, an artist book that I’m preparing with writer John d’Agata around his book “About A Mountain”, which will be published by NY-based publisher Karma. During this I started to keep the palette paper I use to mix the paint for painting on canvases, really just to paint on something other than canvas. I have ended up with more than 500 of these and it’s becoming a larger project than just doing illustrations for the book. I will show these next Spring in Brussels and, hopefully, in NY too.

MC: Your work feels like this incredible dance, can you tell us a little bit about your process of making?

JB: There’s physicality involved, and a lot of wasted energy. Paintings are made on the floor, on the wall, turned upside down, constantly moving until they find their own balance, or their finality, like beyond my will, or despite my intentions. I almost never dance at parties but yes, I am dancing in the studio.

MC: How has your work evolved over the years and where do you see it going?

JB: I just read a text from Roland Barthes about Proust, who is my favorite writer, in which he says that a writer using the “I” (as Proust does) is “below” the literature, opposed to the writers that use the “he” or “she” and are playing with their object like a sculptor plays like clay. For Deleuze, too, in “Proust and Signs”, the book “In Search Of Lost Time” describes a relentless learning. In fact it’s a book about a writer about to write a book. It takes the narrator thousands of pages to finally find the key that will allows himself to write, to finally be a writer, and that’s the end of the book... And for Barthes, each artist needs a key to fully express their art, and the key for Proust is the names. Names of characters, names of lands and villages.

I read In Search Of... more than ten years ago, and also read a lot of books about this very book, and always thought of my work like the same kind of perpetual attempt, which means I could leave room for mistakes and accidents and let a lot of different things coexist in my practice because what was important was just to try. It also helped me to find a structure to my work, each painting is a word, each exhibition a sentence and the whole work is like an ongoing book (a book in progress). But I had never read this Barthes short essay before, and I don’t know if it’s just what I needed right now to understand what’s happening in my work, or maybe that I also need to find solutions and not just drown in endless possibilities, but it suddenly made sense to me that a: I’m still below painting and b: it’s time to search for keys.

I don’t have any idea the way it will happen and even if it will happen, but it looks like I have a new thing to think about when I’m in the studio. But I’m pretty sure the simple idea of acknowledging it already makes me closer to that new aim. So, to summarize my answer, I would say that I think I’m an artist, maybe since I was born, but I’m looking for my key to be a painter, and I have the feeling everyday I am a little more.

MC: I love the unexpected objects like your painted shed, how do you see your work translating through to 3-D objects and will you be exploring this more?

JB: I made a few sculptures a few years ago. It started because I didn’t have enough money to buy new stretchers for a few weeks, so they were carefully made of cardboard and glue, and then spray-painted. I also made a few painted objects, or modified objects and few paintings-based installations. I even made a series of street banners with slogans for a festival in Brussels.

Usually, in a show, the paintings were traditionally on the walls, sometimes a sculpture on a pedestal in the middle of the room. At the time I liked the spatial thing it created, I had the feeling the paintings were revolving around the sculpture, so I guess what interested me was some sort of movement. This movement is hard to express with the squared surface of a painting, because if there is movement it’s like it is happening on the other side of the canvas/window. But thinking again of these sculptures and objects now, in retrospect, I think it was also a way to express more than “just” painting, a way to say “hey, it’s a whole world that is in front of you, not just easel paintings.” It’s still kind of present now, when I frame some paintings for example. It’s a way of showing that I’m aware of the context, of the people and the history. The shed is a very specific project that came from a command. “JB I have this shed by the pool, I would love you to do something on it.” I made several mock-up’s in photoshop, and the best one was when I used one of my paintings as a semi transparent layer over the wooden shed, so that’s what I painted. For me the result is not very different than if you put a painting to dry against a tree in the garden and look at that painting and how it’s beautiful in the nature instead of the white cube.

I am still making painted objects from time to time, or paintings that don't exactly respect the basic canvas on stretcher. For example I made paintings on plaster tiles, and on apple branches dipped in plaster and painted with gouache. There's a difference between these objects like the shed I made and the banners or the first "sculptures", these objects are painted exactly the same way I paint on canvas, so actually for me there's no difference.

MC: How are you finding New York? What prompted the move from Brussels?

JB: New York is a place I love to come to often, and I have had the opportunity to do residencies last year and again this year. I have friends here, it’s a city that gives great energy and opportunities, but I’m still figuring out if I actually want to settle here or not. I like Brussels very much and I hate it at the same time, but at the moment I have the feeling it’s a place where I can work really quietly and comfortably. I could get more in terms of my career in NY that’s for sure, but maybe I don’t want more and maybe I could get more anywhere if I was more ambitious. NYC is a city where you have to be ambitious because everybody comes here for success. I’m not sure success is what I’m looking for. I’m also pretty sure that a long lasting form of success depends more on the quality of the work than the level of ambition.

MC: You did a residency in Marfa in 2010 and you will be back in 2013. Can you tell us a little bit about that initial experience and what you hope to achieve from this next stay?

JB: Yes I spent two months there in late 2010. I’ll be back there this Spring but for a show at Marfa Book Company. This place is magical, and the Chinati people are passionate and devoted to art and it was the best residency I have ever done. They really respect the artists and you don’t have the feeling the artist is just a way for a non-profit to get stipends, or just simply to justify its existence, which happens quite often in residency programmes. Also, you could think that the Judd legacy could be a burden, for example they could invite only artists that are Judd copycats, doing aluminium boxes, but the only thing they really kept from him in the context of the residencies is Judd’s obsession for excellence and this respect for artists. I loved everything there, the landscape, the climate, the people.

MC: You created a book from the last residency didn’t you?

JB: Yeah I am making a book about this 2010 residency with Bunk Edition in France but it’s not out yet! I’m really excited about it though, because at the time I asked 60 people around me to give me a daily “exercise” to fulfil with the idea of making this book like a diary. I didn’t really make my assignments, but I think the book will be funny, mixing these questions with photos and material from my stay. Samuel, If you read this, you know this book must be ready for May 2013 when I go back there!

MC: I read that you have worked with amazing choreographers like Cécile Loyer and Antonio Montanile, are you still doing light and stage design?

JB: I am still working with Cecile. I started working with her more than ten years ago, learning light design on the job. Even if I designed lights and stage for all of her eleven performances, I think my job became more and more about dramaturgy, or to put it in another way, assistant to the choreographer, almost a dramatist. Cecile made solo performances, then duos and the team on tour was really small, basically it was her, me and someone for the administration. So I would say I am more than “just” a light designer, and I am assigned to that role because we were touring together and we needed someone to press the buttons. Now that I have more shows and residencies, I am too busy to tour with the company most of the time. So I try to be as present as I can during the rehearsal and creation, but then on tour someone will do the technique. I have the feeling I’m not traveling enough with my own work yet, at least for short stays, and I really miss the countless journeys we made together to perform.

I also learned a lot about my own work. Before working in theaters I never really thought of the context of the presentation of an artwork. In theaters this context is very visible, and there’s even a kind of a protocol between the viewer and the performer, because you have to pay, to wait in the dark, and it’s for a limited time. I feel it’s hard to identify the same frame in visual art, but at least it’s now part of my thoughts that such frames exist. This is the only way you can keep the necessary distance between yourself and what people see of you through your work.

MC: What is the state of the art scene in Brussels at the moment?

JB: Brussels is a strange city, not big but not small either, not really nice but not really ugly, and it is changing constantly. After 12 years I still don’t really know what this place is but that’s probably why I like it. It’s the European capital, but also one of the poorest cities in Europe, and it is a dangerous city because of social injustice. The space is cheap and available, you can easily find your own place there because it looks likes nothing is permanent, especially the buildings. Obviously that’s exactly what a lot of artists are looking for, that’s also why there are so many in Berlin where space is cheap, but Brussels has the huge advantage of being really close to Paris, Cologne, London, etc. and also has, the legend says, the best collectors in the world.

Also, since the Wiels opened (the contemporary art center) it’s had a very good and edgy international programme and good residencies, the city is more and more attractive, and new artists run spaces, bookstores etc open almost every month. Even here in NY everybody’s talking about Brussels. I even heard just yesterday that some Americans call it the Brooklyn of Europe! That kind of makes sense and I feel it’s great and exciting to be part of it. I wish I was more active myself in developing something toward the public, but I was traveling most of these last years and didn’t have time for that, but it’s in my mind.

MC: Finally, what legacy do you want to leave through your art?

JB: I’m struggling to have a great life, a happy life. I was lucky enough to be able to do what I do, supported by my parents, and also I had very good and interesting day jobs...so I’m not talking about struggling to make a living or being able to “be” an artist, but just a fulfilled human, a committed lover, someone people can rely on, trust, etc. I hope all my desires and intentions and progresses are at the very heart of my work, and that it could someday be read as that and maybe be kind of helpful to others.

That’s why I love art, especially literature and music, because that’s what keeps you alive. Someone made this great song that made my life better and happier for a few days, or that turned this break up into something even worse and more painful. Someone made this movie that told me how to say this thing to my mother, or to my boyfriend. Someone wrote this book that explained to me so many things about love and death and absence and also things about art and being an artist. And someone also painted this painting five hundred years ago and today I am still moved by it, and even before that someone left an imprint of a hand on this cave wall and it is like this was just made yesterday by someone still alive.

This is the greatest thing about art, something nothing else can give you. It surely doesn’t make your life better, especially when it’s your turn to make art, but it makes every one's life more interesting, more intensely lived.

Megan Christiansen

Photographer - Clément Pascal

end