- 1

- 2

- next ›

- last »

Gregarious, with a down to earth nature, Chris Sullivan has the kind of get up and go we mere mortals can only dream of. He's a big chap with a personality to go with it, fond of a lively debate - he's a fiercely proud Welshman through and through. Now in his 50's Sullivan is still quite the man about town, father, husband, writer, documenter, artist, style icon, singer and all round good egg, to top it all his enthusiasm and sincerity about his many passions give him a forward thinking attitude that knows no bounds. Currently, our Mr Sullivan is enjoying a well received response from the recently published book We Can Be Heroes, a photographic reportage by Graham Smith that tells of a time (the late 70's and early 80's) that unbeknownst to its participants set the cornerstones of various creative scenes for decades to come. It's an intimate account with a resonance that in a sense is timeless, a record of a movement that continues to inspire and inform the current climate of flourishing creative movements and I suspect those yet to come.

Princess Julia: Tell us a bit about your background, how you came to be in London and how you became part of the 80's creative scene in London.

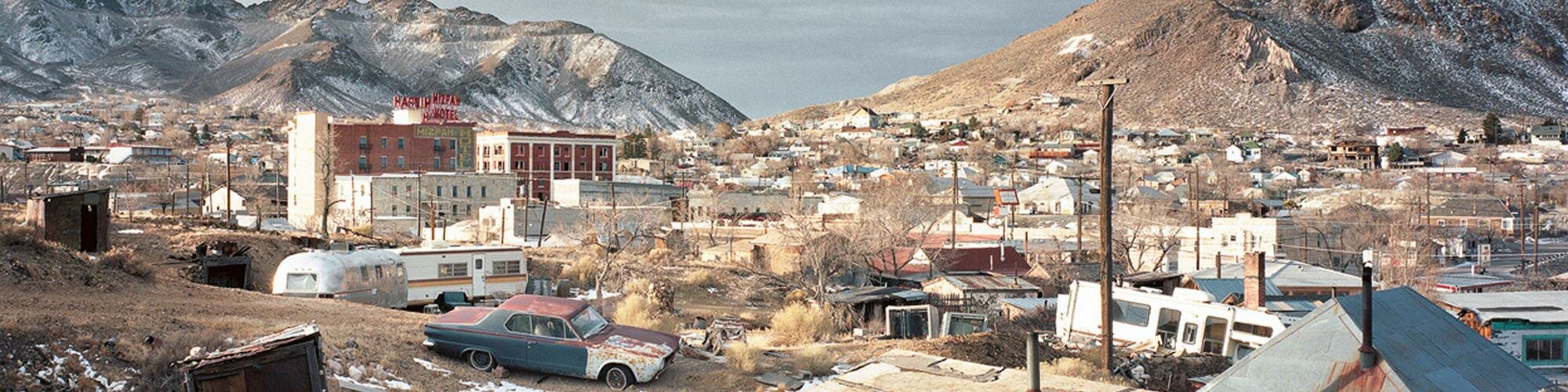

Chris Sullivan: Cor blimey! That’s a long story. I was born and raised in Merthyr Tydfil, South Wales. I was the oldest grandson in a big Irish Catholic Faith and my grandmother (who had an IRA collection box in the hallway) wanted me to be a priest. That still makes me laugh. I came to London first when I was just 15 because I was always fighting in Merthyr with older men who disliked my way of dress (I was into the Bowie Live/ Young American and Roxy Music looks) and was looking for anywhere to go without ripping my trousers. I came and visited clubs like Crackers, Sombrero and Chaguaramas and at first, could not believe that I was in a licensed venue and there was no violence. Even if I wore a hat. Then, as I’d been a Northern Soul dancer because of my dance steps, I fell in with a load of extravagant peacock soul boys in pink peg trousers and Let It Rock mufti, and came here as often as I could afford, often hitchhiking up. I used to walk down the King's Road, drop in Acme and end up in Sex where the lovely Jordan befriended me. I then met the late, great Nils Stevenson who co-managed the Pistols, and I’d call him and he’d inform me of all the best clubs, parties and performances. So I was right in the thick of the punk hierarchy - a 16 year old Welsh kid with an accent so strong no blighter could understand what I said. That continued until 1978 when I received a student grant and enrolled in Camberwell College of Art. When I got here [London] I quickly hooked up with all my old pals, one of whom was Steve Strange who I knew from Wales, and the ball rolled on faster than I ever imagined. The rest is in We Can Be Heroes.

PJ: What were your dreams and aspirations and have they changed over the years?

CS: To get out of Merthyr Tydfil and avoid imprisonment as much as possible. The first has vanished because I live here, but the second is still on my mind although as I have gotten older the only brushes I’ve had with the authorities have been because I put my rubbish out at the wrong times. In truth, my main goal is to do exactly as I please creatively, otherwise not as anarchistic as it might appear; apart from an entire disrespect for money and all those who live their lives by it, I am devastatingly normal.

PJ: You seem to have a multidisciplinary streak to what you get up to, how would you define your career, what is the one constant in your life regarding your creative outlets?

CS: I’d define my career as a search for something that doesn’t get on my nerves, satisfies me creatively and allows me to pay the bills. In many respects I’d have loved to have been a painter, but I found my creativity forever been stymied by extreme poverty and hunger. The one constant has been hard graft. I think you can do anything you want as long as you’re prepared to work really very hard.

PJ: Let's talk about Graham Smith's book We Can Be Heroes and your involvement in it, what fascinated you about his photographs?

CS: That I was in most of them... No, really I just thought that that particular scene depicted in the book that we were so involved in, had always been much maligned and misunderstood, and so I felt that I should, as I did with my other book, Punk, set the record straight. Graham asked me to write the text because, apart from Bob Elms and your good self, I am the only writer who was there in the thick of it and knew the ups downs and around the corner of the whole shebang. Graham’s photos are rather like those of my old friends Nat Finkelstein, Billy Name and Danny Fields who shot the Warhol Factory and the early NYC punk stuff. This led me to compare the two scenes and I thought ours was as valid and as interesting and as barking as Warhol’s, so I thought it had to be recorded. A lot of this social history is recorded with such seriousness I thought I had to illustrate in words just how much of a grin it was – from here to here as it were.

PJ: How do you think they relate to today's scenes?

CS: I really can’t say. I don’t hang out that much in today’s equivalent purely because I find getting home to Maida Vale from Hackney at 4am a real pain in the arse. What I have seen though doesn’t compare to the sheer extravagance (dress wise) that we enjoyed and they don’t seem to be as mixed. Although I could be wrong. I remember Mathew Glamorre’s Kashpoint was as excessive, so perhaps there still is. We had straight and gay, black, white, Asians, cross dressers, bruisers, bus drivers, bodybuilders, alongside aristocrats, artists and assholes, all under one roof. I don’t see much of that in one room anymore, but then again I don’t go in search of it. I hope I’m wrong though and hope that it does exist.

PJ: Your book 2001 book Punk with Stephen Colegrave documents life before the New Romantic era, was We Can Be Heroes a natural progression for you to get your teeth into?

CS: It certainly was. Charting my cultural past as it were, but also getting testimony from all those involved so it wasn’t just my voice. The Punk book was red, black and white, and was an oral history with additional text by me and so is this. I like the continuity as one might buy the pair and get a handle on what went on as told by those who did it. I might do 1985 to 1994 next.

PJ: Club life has been a continuing feature in your life, what is it about it that charms you so much?

CS: I’ll quote myself here from an article that I penned for The Times. "As a teenager in the seventies the nightclub was all. We’d been raised watching classic film noir on TV that, filled with monochrome images of smoke filled dives frequented by wisecracking detectives, sulky divas and fatal femme fatales were grist to our chill. Even the music we listened to – Roxy Music’s Do The Strand, Bowie’s Life on Mars and Lou Reed’s Walk on The Wild Side seemed to inhabit this twilight world that we longed for. We believed that nightclubs were where one would meet one’s fortune, fate and failings.”

Clubs were where the people I was attracted to hung out and not the pub. People dressed up and danced and went home with each other. I liked all of that. I met all my great friends in nightclubs. I also like that race, colour or creed doesn't exist in the right clubs; as as a rule you have decided to be there, paid to get in, and are up for broadening your horizons.

PJ: How has your scene evolved from your early nights such as Le Kilt and The Wag to the present?

CS: Le Kilt was where we really hammered home the funk (which few were into apart from us at the time) and at The Wag I continued the same ethic. I feel I live in this ivory tower and try not to be influenced, tending to rely entirely on my own opinion that is unfettered by any body else’s influence.

PJ: Let's talk about your personal style; you have always had a very precise look preferring a tailored style, classic and very dapper.

CS: I’m 6' 2" and have a 46" chest, so that has always dictated what I wear. I think a big bloke looks best in classic sharp vintage tailoring, casual forties and fifties American or classic workwear. I do the jeans bit, but only wear Levis 501 XX, Type 2 jackets, vintage leather jackets, Redwing boots, wingtips – all that. The one good thing about being an old bastard is that by the time you’re my age you have worked out what suits you and what doesn’t and tend not to make that many mistakes. I have bought the odd thing outside of my comfort zone when drunk or under the influence of drugs, but never wear them.

PJ: Do you have a favourite era of style?

CS: In the past I've dallied with the style of each decade from 1910 up to 1970 and then I get bored, move on, and put a load of clothes in the cupboard until the fancy takes me to wear them again. At present I like 1930’s French style – newsboy caps, collarless shirts, three-piece suits and baggy (26” wide) trousers. I also love the style of the Parisian Apache gangs of the 1900’s (see the film Casque D’Or by Jacques Becker) but am working on that.

PJ: In regards to music and your role in that, Blue Rondo A La Turk was your seminal band in the 80's, what is your memory of those times?

CS: I started the band to see if I could do it and had very little experience at all - never recorded my voice or sang properly. Less than a year later we were in The Face and a few months later on the cover. Then we signed this big deal with Virgin Records and were expected to have a number one record with our first single which was released in December when all the big guns were away. We were the second most played record on Radio One, the first being David Bowie and Freddie Mercury with Under Pressure. We hit number 29 and were due to go on Top of The Pops which was the only route to the top then and usually bands got on if in the top fifty, but we were sidelined because there is a stipulation that any BBC recording artist got on the show no matter the chart entry, so Ken Dodd went on instead of us with Hold My Hand which peaked at 75. This one chink sort of screwed it really as Virgin wanted pop hits and unfortunately I never designed the band to be ‘pop’, so our next single had a hook line that was a series of grunts and a totally unpronounceable title Klactoveesedstein (http://soundcloud.com/chris-sullivan-3/klacto-instrumentalist). Virgin completely balls’d the marketing by not having enough records in the shops on day of release, but it still sold a quarter of a million copies and was in the charts for 6 months. We were a gang of mad-arsed bastards, being treated like kings all over the world - we had number ones all over Europe - and touring constantly.

PJ: What has been your proudest moment or moments?

CS: I’ve had a lot of those. Getting into Central Saint Martins, signing a huge record deal with Virgin, opening The Wag seven nights a week, seeing the video I directed on the telly, having my first art exhibition sell out, getting my first cover article for The Times Magazine. Perhaps my proudest moments are embodied in my seven year old son, Finbar, who is such a lovely, compassionate, affectionate child that he fills me with pride. Of course Leah, my other half, plays a massive part in this, but I like to think I had a hand in it.

PJ: What advice would you give the younger generation? Indeed do you feel a generation gap at all?

CS: Take no notice of what anyone tells you, do unto others as you’d like done to yourself, to thine own self be true, don't become a slave to possessions because after a while they will own you, try and have a few kids, but wait until you hit 40, look after your teeth, try to learn as much about everything as is possible and don’t listen to people like me. All the clichés really. I don’t really feel a generation gap as I exist in my own bubble and take absolutely no notice of trends, fashion, older or younger people or the world around me. I think I am more like a reactionary sponge who involuntarily soaks up influence without knowing how or why, and haven't the self discipline to not react. I wish the younger generation were a little more aggressive politically, angrier in general and not so celebrity obsessed.

PJ: What projects have you got coming up? Do you feel you've achieved everything you've set out to do? Do you plan things or have a spontaneous attitude to life?

CS: I have had a film script called Anarchy In The UK (nothing to do with Punk rock) optioned by a Hollywood independent so I hope that will be made next year. I’ve just co-written an 8-part series for The Crime Channel called Who Ran Britain presented by Martin and Gary Kemp and hope to start working on another doco idea with Suggs. I am about to write a book called Sullivan’s Travels about all the mad trips I’ve been on, some as a travel journalist and others as a traveller. It was a friend's idea as mad shit always happens to me as soon as I pick up my passport. I’ve been arrested in Paris, Tokyo, Zanzibar, San Francisco, Berlin, and Bournemouth, and ended up in the worst and best places any human might end up in. So it’s a book waiting to be penned.

Photos: courtesy Chris Sullivan, taken from We Can Be Heroes

Download Chris Sullivan mixes and DJ sets here.

Chris Sullivan's new book We Can Be Heroes, can be purchased here.

Princess Julia

end