- 1

- 2

- next ›

- last »

For Canadian photographer Jeff Wall, the visual intricacy of cinematography plays a heavy influence on his large scale works which encase a similar element of poetic complexity. Each photograph is staged and recreated from a memory of a previous occurrence and moment experienced, or an enhanced scenario.

Currently on at the National Gallery of Victoria, the exhibition 'Photographs' showcases Wall's work spanning 1978-2010, featuring 26 encompassing and iconic photographs from the artist's career. In a gallery space, they are fascinating and intriguing, their large figures seem to dominate their presence and there is an element of seduction as they are each illuminated and encased in light boxes.

This unique perspective is Wall's recognisable style. The photographs make you look twice, longer and deeper, furthermore subconsciously encouraging you to find your own relatability to the image and for a moment pondering your own daily nuances and interactions. Wall has certainly played a key role in discussion of photography as a contemporary art form. Coming from a background in painting, there is a distinct inspiration in his works from Édouard Manet and Hokusai, and a contemporary interest in writers such as Ralph Ellison, through which seeps an influence of artistic reference into his iconic photographs; A Sudden Gust of Wind (After Hokusai) 1993, and After “Invisible Man” by Ralph Ellison, the Preface (1999–2001).

'Photographs' is currently showing at NGV Australia, in conjunction with Berlin photographer Thomas Demand's current exhibition - a suitable match of complementary recreated photography. While Wall was in Melbourne to open the show, we sat down with him as he poetically explained his recreated photographs.

Joanna Kawecki: I can imagine your intuition plays a big part in your work.

Jeff Wall: I think it's the freedom. One of the most things I like about my so-called method for my photography, is that I have a lot of freedom. I'm not bound to there even being an occurrence. I can just pretend there was an occurrence, or I can have a relation to a real occurrence, or I can blend the two. That creates a kind of freedom that I find very much like a poet, or composer, or even a painter. I like the fact that photography could have that freedom at least in terms of where its first impulse comes. It doesn't always have to be reportage, although reportage is gonna be there all the time, and I can use it anytime I need to. So that memory creates a sort of a free space.

JK: It has been now 33 years now since you took 'Picture For Women' (1979), which has been the subject of many discussions to say the least.

JW: Yes, in fact I was 33 years old then when that picture was taken, and now we're here 33 years later.

JK: Very serendipitous.

JW: Feels like I've been 33 twice now!

JK: There are many discussions based on this photograph, whether it's feminism, or a different theory surrounding it. Firstly, what was your initial thoughts behind creating the image, and secondly, do you still feel that same way 33 years later about the image?

JW: Do I feel the way I felt then? I couldn't, because its 33 years later, and things have changed. So I can't feel the same, and I couldn't have felt the same after I had made it as I had felt before I made it, and when I was making it, because once I'd made it, I changed my relationship to it because I'd done it. So I look back at it to see whether I feel it still measures up. As I was saying yesterday, whether it measures up to some judgement, that could make up it's goodness. That's something I do all the time, and that is the most compelling thing to me. Do I still think it's any good, and was it worth doing in the first place, and so on. That's more important to me than what it might have meant then or now, to me. I don't think I could really tell what it might have meant at the time. I wanted to work in the studio, it was one of the first few pictures I managed to do when I really started to get active, and I was into the studio as a space. Like the way that Thomas Demand had mentioned that he was essentially photographing the inside of a studio. It's fascinating to me, because I realised, that's what I was doing. Furthermore, in order to be in that studio, you had to make something occur there, to bring something there, it's empty otherwise.

JK: And you took accompanying influences from art and painting...

JW: Yes, for all sorts of reasons I wanted to bring photography together with that, with painting. Then with that painting by Monet, which I'd seen for many many years or at least many, many times over 3 years, that painting had meant a lot to me. For artistic reasons, and personal reasons I guess, and so it was once of those clusters of things that ended up making, resolving itself to do a picture that said something about photography too, because of course there's a mirror and a camera, and there's a subject and theres the perspective, which people have commented on because they love talking about those kind of conundrums of who's looking into it.

JK: You've previously questioned the lifespan of an artwork and what might be the quality for it to supersede generations of works. So I guess in that way, from your work how long do you want to make it last?

JW: I want to make it physically capable of lasting an extremely long time because then it gets a chance. The chance being that people will continue to like it, to continue to judge it to be good, and include it in their repertoire of art they'd like to keep seeing, and maybe generations can do that. That's what most artists probably expect if they have any expectations at all. It's that people keep liking their work and they'll become somebody. And if your work doesn't last, that can't happen. So I've always been sort of devoted to the ideas of ways to make my work survive.

JK: Do you think then although on a lower budget and less resources, it is more admirable for someone to create something incredible with less resources than someone who has more?

JW: No, because sometimes having more makes everything harder. Because we have much more to manage, the inertia is enormous, so if you make a decision you go in a certain direction and it's not a good one. It's very hard to change directions at that point. So no, I think it's just as hard to be good when you're young as when you're old, just as hard to be good when you have little resources, as when you have a lot. It's always the same, it's just how you work with what you have.

JK: With your show in Melbourne, Gary Dufour was the main curator, and he worked within the size of the exhibition space to select your work shown. Was there any compromise to the selection?

JW: I wouldn't say compromised, but shaped. We kind of created a show that worked within the parameters that we had.

JK: What do you feel about the selection? Is there a certain way you'd like to viewers to view the works, or a certain feeling for them to depart with?

JW: I don't think I can say that, because it's really not up to me. All I really hope for, is that they think they're good works. That they think it's good work that I do. And they've enjoyed it, and that they've gotten something from it, and that perhaps they class it amongst the good art.

Full interview in see Ala Champfest Issue #6

CREDITS:

1. A sudden gust of wind (after Hokusai) 1993

2. After ‘Invisible Man’ by Ralph Ellison, the Prologue 1999–2000

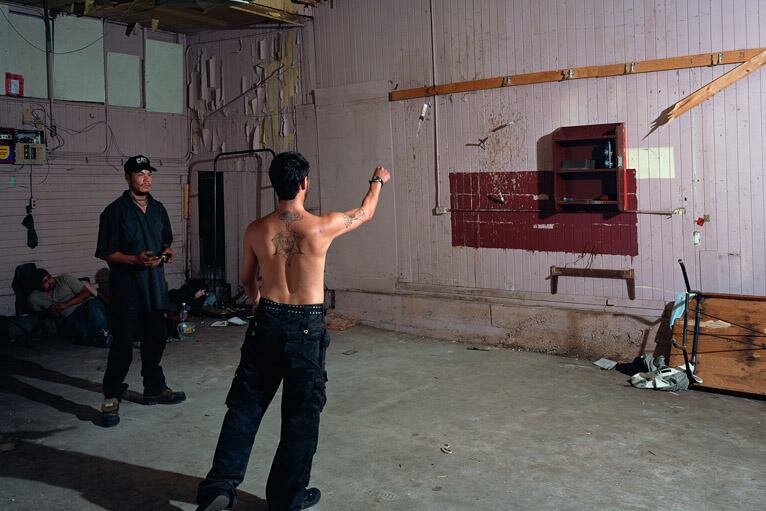

3. Knife throw 2008

4. Double Self-Portrait 1979

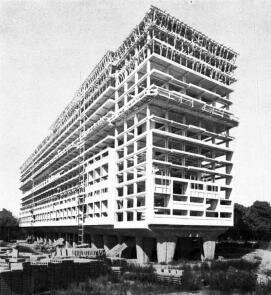

5. The Destroyed Room 1978

All photos: © Jeff Wall

Joanna Kawecki

end